Genetics and Genealogy

This page provides complete information about the genealogy and genetics of every Eastern Indigo snake in the future Impeccable Indigos breeding colony.

The only way to protect the quality and the future of captive-bred Indigo Snakes is for breeders to engage in transparency and full disclosure. Information is the greatest protection for the species, hobbyists, and breeders alike.

Responsible breeders have nothing to hide and this page is proof. We encourage others to do the same.

Understanding Indigo Genetics

The costs of legal protection

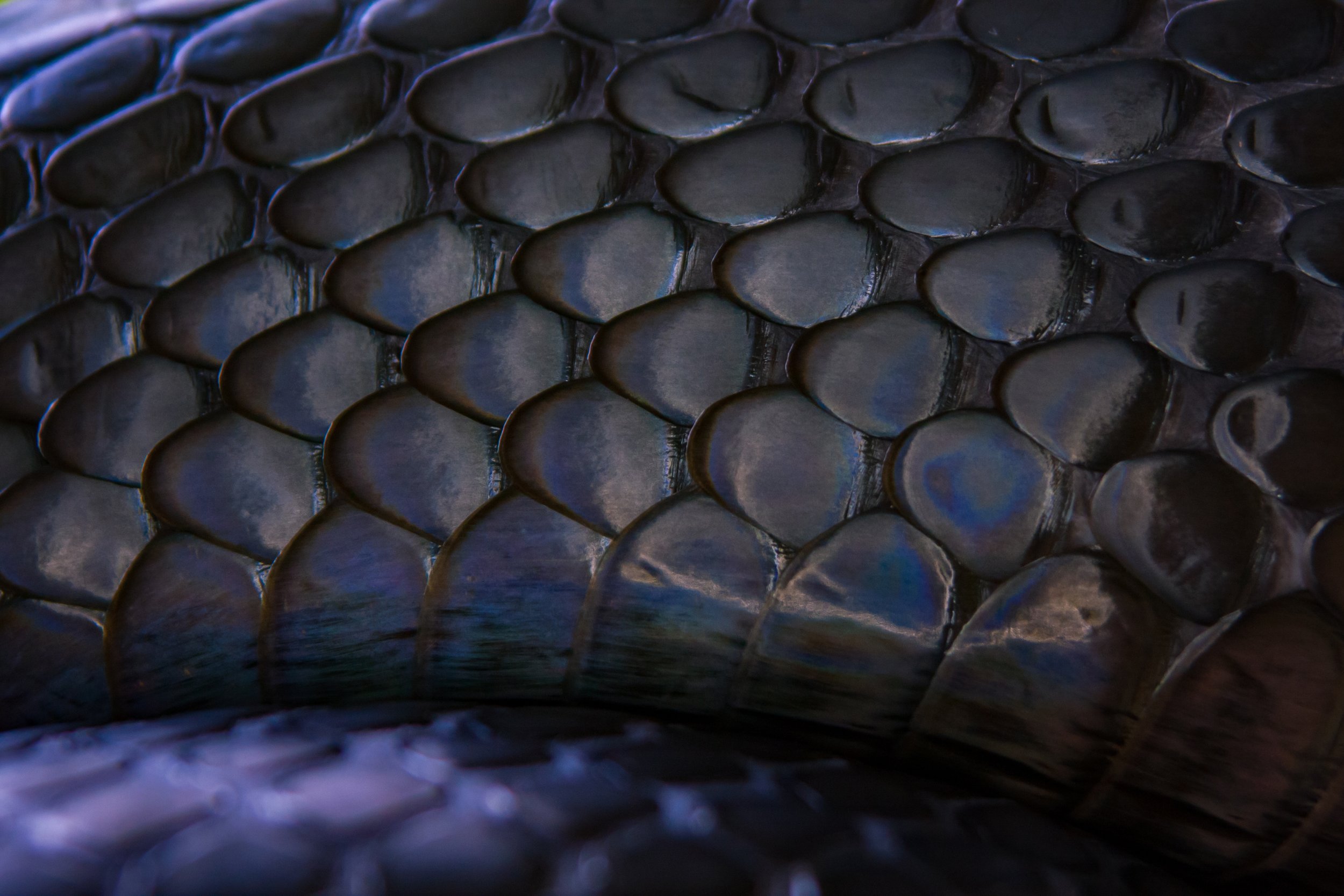

When the Eastern Indigo Snake was federally listed in 1978, it effectively froze the available gene pool at a time when the species was at a low population. The result is that today every wild Eastern Indigo is assuredly related, at least to some degree, to every other wild Eastern Indigo.

And of course the impact on the captive bred gene pool was the same, if not more significant, because it was and is an even smaller population. There is no doubt that, particularly in the early years of protection, there was significant poaching, and wild specimens were contributing some genetic variation to the captive pool. But while speculation remains as to the extent of wild poaching today, it is certainly far less common and likely no longer a significant factor in varying the captive gene pool, as the occasional introduction of a few wild individuals would not impact the captive population as a whole. As with the wild population, every captive bred Eastern Indigo is related, to at least some degree, to every other captive bred Eastern Indigo.

Certainly the various agencies and organizations currently involved in captive breeding and reintroducing the Eastern Indigo to portions of its former range are keeping extremely careful track of the genetic diversity of their breed-and-release animals, albeit unfortunately they are not publishing those details. We must assume that these various entities (including: US Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS], Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources [ALDCNR], Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission [FWC], Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens, Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation, Orianne Society, Auburn University, The Nature Conservancy, US Forest Service, Zoo Atlanta, Welaka National Fish Hatchery, Zoo Tampa, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia Sea Turtle Center, Alabama Natural Heritage Museum, and others [Ref: Central Florida Zoo: About the Zoo]) are doing their utmost to maintain genetic diversity and avoid extreme inbreeding. Unfortunately to date neither these organizations nor federal or state Fish & Wildlife agencies have shown the slightest interest in engaging with the captive breeding community. Both communities — and more importantly, the species itself — could mutually benefit from cooperation, but unfortunately we are at present left to merely imagine such future interactions. Imagine, for example, if sperm samples from wild populations could be used to artificially inseminate captive populations, to freshen and vary the captive gene pool? No doubt a handful of breeders would pay significant fees, that those in charge of managing the species in the wild could doubtless put to good use. The mind boggles.

Meanwhile we can only speculate as to the degree of inbreeding within the captive bred population. At first these issues were not at the forefront of awareness among the tiny community of captive breeders. I certainly wasn’t thinking about it when I first bred my wild-caught specimens in the early 1970s. It seems likely that captive breeders, selecting at face value for traits like size and color, were at least for a time engaging in some degree of indiscriminate inbreeding and “line breeding,” that is, deliberately breeding offspring back to the previous generation in an effort to produce animals with desirable traits.

In more recent years, however, concerns and awareness have grown, and respected breeders have clearly made an effort to consider relatedness when choosing pairings. Much speculation and mythology is repeated in online groups about faulty traits such as spinal kinks, split ventral scales, and dwarfism, yet the science is lacking as to which if any of these traits are actually due to inbreeding versus incubation issues, an entirely different matter. Wild charges are sometimes circulated against this breeder or that, often depending as much or more on grudges and other personal antipathies rather than falsifiable evidence, and yet in some extreme corners such innuendoes are taken as fact rather than myth, and science rather than mere gossip.

Most responsible veteran breeders are open with their customers, sharing some degree of information about their collections and histories. When a breeder claims to be maintaining diverse genetic lines, the customer relies on reputation and relationship when making a judgment call, while some at greater distance are eager to offer critiques and complaints.

One change that has had an impact is the existence of a genetic testing program developed by Therion International LLC who, according to their website, “is the recognized leader in providing reliable and accurate DNA-based testing services for addressing questions concerning the genetic identity of animals.” The Therion genetic testing for Drymarchon species was developed in an exclusive business relationship with Mr. Alan Brutosky, who charges a fee and serves as intermediary between his customers seeking testing and Therion who actually performs the tests. Presumably, several hundred specimens have been tested since the program began. As of mid-2023, however, reports indicate that the owners of Therion are retiring and closing the lab. Time will tell if another lab picks up where Therion leaves off, but we can safely assume such efforts are underway.

In brief, the Therion testing looks at 10 pairs (originally it was 11) of alleles, or pairs of genes, characteristic of Drymarchon DNA. This test represents a small fraction of the genome of this genus and species, which have yet to be completely mapped, but so far this is a better-than-nothing approach that provides information about relatedness between individual specimens. This is independent of identifying actual genetic traits, and selecting for healthy traits versus unhealthy traits is actually of greater concern in the eyes of many experts, because we know that pairings with high relatedness can produce perfect offsprings, while pairings with low relatedness can produce flawed offspring. While some would insist that the 10 allele pairs currently being tested by Therion are the end all and be all of genetic issues in breeding Eastern Indigos, the truth is otherwise and far more complex. As the saying goes: Every problem has a simple solution, and it’s usually wrong. It is not my intention to elucidate all of these issues here, but merely try to identify them in simplified form.

The game changer in this regard will be DNA testing by Rare Genetics, Inc., the company founded by genetics tech entrepreneur Benson H. Morrill, PhD. Rare Genetics currently provides low-cost DNA testing to identify sex in a wide range of snake species. But they are actively engaged in dramatically expanding their range of abilities, and are now identifying morph DNA in Ball Pythons. This development will undoubtedly serve to dramatically transform the captive breeding industry in the next few years, because buyers will no longer have to take a vendor’s word for what the snake they are buying at an expo is “het” for or not when it comes to non-expressed traits. Times change.

Further, Rare Genetics is hard at work on mapping complete genomes for multiple species — including Drymarchon couperi and other Drymarchon species! — so as to be able to determine relatedness, and create large databases similar to what firms like 23andMe now offer in tracking human DNA and family trees. It’s only a matter of time before Rare Genetics will be able to test Drymarchon for far more than a mere 10 pairs of alleles.

This material is intended as a brief summary introduction to what is a complex and sometimes controversial subject. As I discuss in Chapter 4 on the Husbandry page, buyers need to do their due diligence, develop relationships with responsible breeders, and use their best judgment when choosing a source. Reputation, longevity, experience, expertise, and of course the actual quality of animals, all must play a factor in making these decisions. And see the Resources page for a number of informative articles about snake genetics.

IRIS

“IRIS” — 2020 Red Phase Female

Produced by Robert Bruce

Eventually, genetics and genealogy will be posted here for all Impeccable Indigos. However, we begin with this interesting specimen, which has been tested twice by Therion, with identical results both times. Typically two or three matching alleles is considered good in the current gene pool, and the general opinion is that wild specimens from the current native population of D. couperi would typically show as three matching alleles if not more. Many of the best breeders believe it is perfectly acceptable to breed animals with four or five matching pairs, as long as these pairs are significantly different between the two animals. In this way, pairings are kept to a relative low percentage of relatedness, and if that percentage is between 20 to 30 percent it is considered very good.

This particular animal shows zero matching alleles amid ten results; one marker, #61, is blank, a common problem with this testing procedure. Due to the missing result, this snake shows zero matches out of ten, or potentially one match out of 11 if it was turn out that 61 is a matched pair.

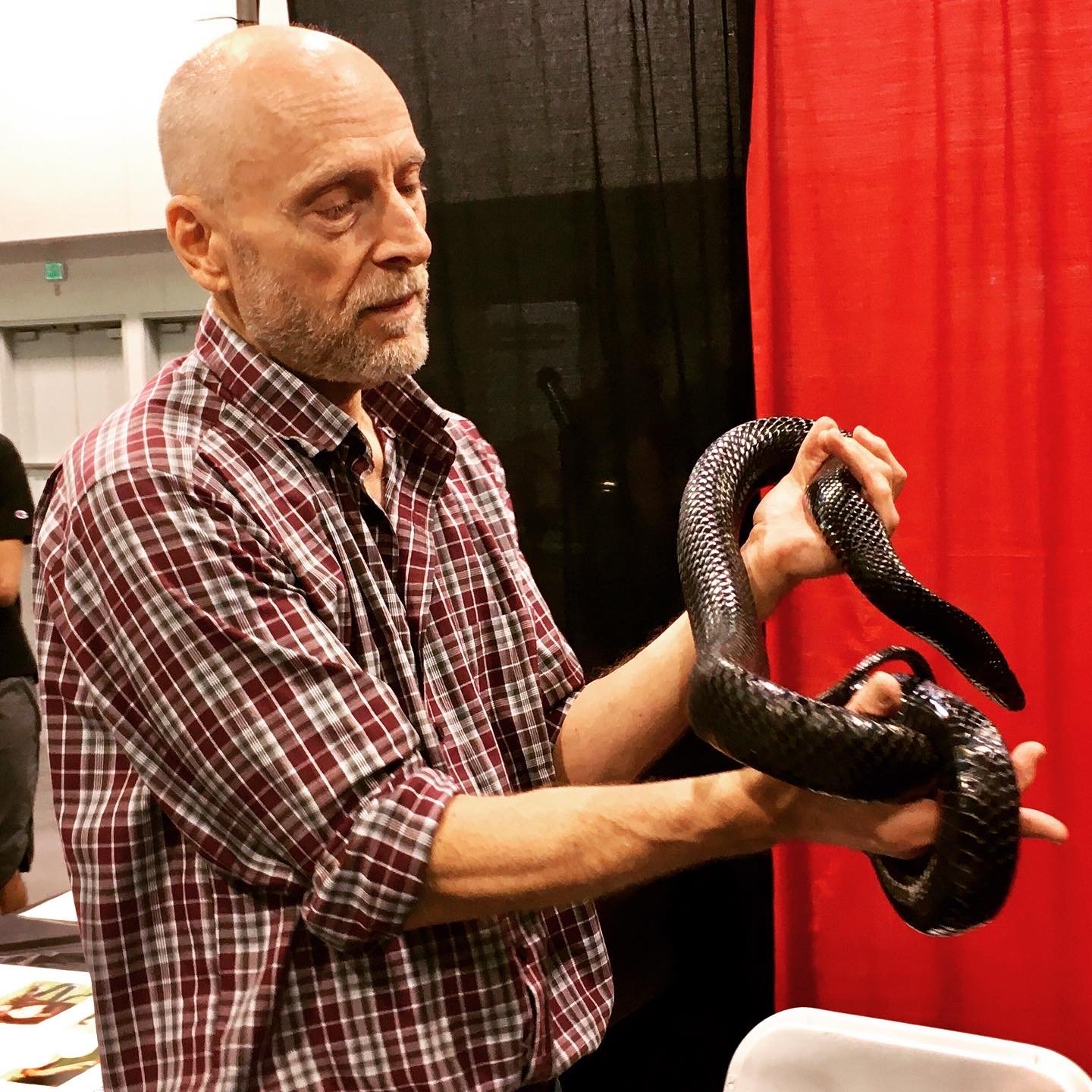

This is a clearly notable specimen and to date no experienced breeder I have spoken with has seen another with results like this. What makes this even more interesting — and this is not a commercial of any sort, it is simply interesting and useful information — is that this animal was produced by Robert Bruce.

Mr. Bruce, based in Southern California, maintains the largest and most longstanding breeding colony of exclusively D. couperi. He has long maintained that when he began his breeding program some twenty years ago he started out with a number of diverse lines gathered from many different sources, and that he has maintained careful records throughout, enabling him to breed and sell pairs of low relatedness. Mr. Bruce has a number of vocal critics who insist that his claims are erroneous at best if not actually false. And yet, here is a specimen possessing unarguably extraordinary genetics. Make of this what you will, but I intend to make beautiful snakes with the help of this remarkable animal, produced by Robert Bruce.

Robert Bruce

OTHELLO

“OTHELLO” — 2021 Red Phase Male

Produced by John Michels (Black Pearl Reptiles)

Othello’s genealogy

Provided by John Michels & Black Pearl Reptiles

HATCH DATE: 8/26/21

OTHELLO’S PARENTS:

The sire is “Cooper”. Produced in 2017 by Black Pearl from a Matt Rand x Andy Watson breeding: Mr. Peabody x Connolly

COOPER PARENTS:

Mr. Peabody (sire): Acquired from Gayle Foland in 2014 as adult. Produced by Matt Rand

Connolly (dam): Produced by Andy Watson in 2013.

Connolly sire produced by Brutosky 2008 from Kruse (Bronx Zoo)/Alessandrini x Fuller 2006 (Mr. Mullett Fingers x Sister Sink)

The dam is “Kit”. Produced by Jeff Jones from Virgil Willis lineage in 2009. (Kit parents are unknown.)

KIT PARENTS: unknown

There is no connection to Robert Bruce animals dating back three generations. DNA testing indicates 22% relatedness to Iris for future intended breeding by Impeccable Indigos.

John Michels & Chris Rodriguez of Black Pearl Reptiles

NOIR

“NOIR” — 2021 Black Phase Female

Produced by Robert Bruce

DAHLIA

“DAHLIA” — 2021 Red Phase Female

Produced by Vic Herrick

Dahlia’s genealogy

Provided by Vic Herrick

HATCH DATE: 8.1.22

DAHLIA’S PARENTS:

SIRE: Nandi (dark phase male)

Nandi is a large, long-headed handsome dark phase male. Nandi’s sire was a dark phase, thought to be (not confirmed) of Robert Seibs, formerly active breeder in California. Nandi’s dam was a red phase belonging to Vic Herrick, bred by Robert Harper who bought it from Matt Rand. She was known to me as “Tempest Storm”; speculated to have been produced of Dean Allesandrini stock. (All of this research tends to bring us to a few names of potential founder stock: i.e., Allesandrini, Bruce, Kruse, Seib, Takata, Bordner, and a few others known. Robert Harper is a high school chemistry teacher near Stockton, CA, who bred Indigos for a time, primarily from Robert Bruce stock, but eventually left the endeavor.)

DAM: Carmen (red phase female)

A daughter of Ramses (retired from breeding and now in possession of Tek Watts). Ramses was of Robert Bruce origin, roughly 20 years ago. (When tested, Ramses appeared to be closely related and possibly sibling of Mandingo (well known Vic Herrick male, see guest gallery). Ramses is a big, robust red phase. Carmen’s dam was Nefertiti, a red phase of Robert Bruce origin. (Now deceased.)

Vic Herrick

OBERON

“OBERON” — 2023 Black Phase Male

Produced by Brad McCarthy

Oberon’s genealogy

Provided by Christopher Daniel

HATCH DATE: 7.8.23

OBERON’S PARENTS:

SIRE: (dark phase male)

Produced by Brad McCarthy

DAM: (dark phase female)

Produced by Steve Binnig