Husbandry

Welcome to Impeccable Indigos.

Celebrating North America’s most charismatic snake.

This website is a work in progress. If you have compliments, criticism, correction or complaint, please use the contact form to let us know. We welcome your constructive suggestions, including recommendations and referrals to worthwhile content you think we should add in the Resources or Husbandry sections. Let us know what you think!

We love Indigos!

…. and all Cribos and Drymarchon too!

Care and Maintenance of Indigo Snakes

… and all Drymarchon species

These husbandry pages amount in essence to an online book: Impeccable Indigos: The Care and Maintenance of Drymarchon couperi in Captivity, by Jamy Ian Swiss. Like any good book, you won’t read it all in one sitting. But I hope readers and researchers, hobbyists with a single pet Indigo and breeders with multiple generations, as well as those keeping or interested in Cribos and all Drymarchon species, will explore the material, read and consider it, and above all use it. I sincerely hope you’ll stick around here for a while, because above all, that’s why this site is here. And if you have questions, clarifications, or constructive criticisms, please don’t hesitate to use the CONTACT button and get in touch. Welcome!

-

a philosophy of reptile husbandry

“The bad old days of ‘rack ’em high, breed ’em fast’ are over. Super sterile enclosures that do nothing for mental or physical enrichment are fading away quickly as we start to walk headlong into an exciting era of high education and thoughtful, accurate supply. We must, as modern keepers, grasp the fact that it is far better to care for a small number of animals and to provide them with the ability to behave naturally than it is to overreach ourselves with huge collections and fall into the trap of providing our collections with ‘minimum standards’. The watchwords must be ‘ethical care equates to effective care’.” — John Courteney-Smith, The Sun: Its Use & Replication within Reptile Keeping

In recent years, since returning to the hobby of snake-keeping in general and Indigo Snakes in particular, I have learned a great deal more than we knew when I was first in the hobby and the industry decades ago. The herptile hobby has exploded with increasing popularity, accompanied by massive quantities of freshly minted information and scientific research, along with new technology and equipment for keeping reptiles that wasn’t available a decade ago, and in many cases, even five years ago. From heating, lighting and enclosures to breeding, behavior and enrichment, we not only know more than we have ever known before, but we are literally continuing to discover and learn more every day. While it is my intention to provide husbandry information and guidance that reflects the latest trends and data, I want to begin by acknowledging that there is a new school of thought afoot in the reptile keeping world, that departs from many of the old ways. It is not merely that “folklore husbandry” is being replaced by science-based guidance, but there is also a growing conflict between old school and new school assumptions and approaches, that might be most cogently summarized as the difference between two different sets of goals and guiding principles, namely the difference between:

SURVIVE versus THRIVE

Old School: SURVIVE

Consistent survival of animals and meeting fundamental physical health requirements is sufficient for quality captive care and maintenance over the long term. Animals can survive and even breed in small enclosures, rack systems, unnatural conditions, limited monoculture diets, minimum and often only ambient heating, and no UVB lighting.

New School: THRIVE

Survival and fundamental health are insufficient standards for captive care of reptiles. Reptiles should be kept in the very best conditions we are capable of providing, including the larger the enclosures the better, naturalistic settings that attempt to imitate native habitat and encourage natural behavior (tunneling, climbing, etc.), added enrichment, the best diet, basking and belly heat, temperature and heating gradients, appropriate (often multiple) hides, UVB lighting, and approximating a natural daily and possibly seasonal light cycle. This simple set of definitions is not intended as an attack on the old school, nor an attempt to paint commercial breeders with a single broad brush. I try to take a broad-minded, fair-minded approach in the materials and guidance that follows. But before I do, the most important conclusion I have come to in considering these issues is that the reptile hobby needs to reframe its approach, attitude, and vision—indeed, its fundamental culture. I believe that the culture of reptile keeping should adopt as its primary operative principle:

CONNECTION – NOT COLLECTION

I understand the desire and appeal of collecting reptiles. When I moved into my first apartment, two weeks after I turned 19, I had one snake – a Florida Chain King (Lampropeltis getula floridana, aka brooksi at the time), which I had purchased (decidedly against my mother’s wishes) when I was fifteen. A year after moving out I had 28 snakes, six tarantulas, and more on the way. I kept Paradise snakes, four types of Tree Boas, a breeding pair of common Boa Constrictors, a large Reticulated Python (who would reach about 12 feet), and eventually a breeding pair of Eastern Indigo Snakes. I understand the temptation, the desire, and the appeal of collecting. With every addition to the collection, we can’t help but think about what we might add next. For myself, I love all the Drymarchon species, especially Eastern Indigo Snakes and Blacktail and Yellowtail Cribos; Old World rat snakes including Tiger Rat Snakes and Blue Beauty Snakes; some of the mild rear-fanged species like Mangrove Snakes; and Emerald Tree Boas. I admire these species longingly whenever I see them. Snakes are infinite in their variability, beauty, and cause for fascination. I get it. But with our dramatically increased knowledge about what it takes to create conditions that allow our reptiles to not merely survive but rather to thrive, I believe hobbyists need to have a serious reckoning with themselves about the limits of their resources, including space, money, time, and effort. And about whether their priorities lie first with themselves and their desires, or with their animals, for whom they assume responsibility once they put down their dollars and bring another purchase home. The more animals you keep, the more you become a collector rather than a connector. If you have one, two, three, or four animals, you stand a strong chance of working toward keeping them in the very best conditions, conditions that would be the envy of many zoo reptile houses. And the more you create these conditions, the more your animals thrive, your more pleasure you will both get from the experience, because the best conditions lead to animals that are more interesting to watch and interact with, that exhibit more varied and natural behaviors. How much better is it to be able to thoroughly connect with a select few animals than to have a collection of animals in racks of tubs or even small glass enclosures but for which you are unable to provide the very best care and conditions, much less have time to focus and appreciate each and every one of them? I do not consider myself an animal rights radical. I believe in the pleasures of keeping reptiles as a personal hobby; I believe in the existence of zoos as educational and scientific institutions (but not merely as places of entertainment—please boycott Sea World until the day comes we can legally shut them all down). But I have come to believe that the old school of reptile husbandry reflects assumptions that are no longer applicable and, in the near future, will come to be generally regarded as unacceptable. I propose that we all stop thinking about collecting, and focus on connecting with our animals. And if we do this, the hobby will grow healthier, and its reputation will improve, as will the lives of every animal in our care, and every keeper caring for them. I am not a person trying to end or restrict the reptile hobby. I want the hobby to thrive, not just survive—just like our animals. So, I ask you please, to consider a new way of thinking and approaching our shared passion. Think:

CONNECTION – NOT COLLECTION

-

I am not a big fan of so-called “care sheets.” I suppose they have their place, but they should be labeled along the lines of “A Brief Introduction to Care Basics.” The current state of affairs renders many care sheets hazardous, because keepers—especially prospective future hobbyist and newbies—are often inclined to mistake the care sheet for the whole story rather than see it as a summary outline. Care sheets are at best a place to start, but should never represent where you end in terms of learning how to care for captive herptiles.

Hence this page should in no way be considered any sort of definitive care sheet, but rather, despite its length, an abbreviated introduction to the care and requirements of Eastern Indigo Snakes.

What’s more, I often find myself thinking of the words of John Michels of Black Pearl Reptiles, who has said to me (on more than one occasion), in essence: “I don’t believe there is one correct way of doing things. I can tell you what has worked for me. If something different works for you, that’s great. And I’m always willing to learn.”

While I imagine I will update and tweak this page many times in the years to come, I hope to continue to remind myself of John’s words. It’s true that in science we can establish testable truths, and I am someone who is very much about the scientific method, replicable results, and data—wherever and whenever possible. By the same token, there are times when we don’t yet have the data—let’s face it, herpetoculture science is young and in many areas still slender—and so we have to combine the available science with expertise, experience, and our own best reasoning abilities, and sometimes come to a best guess decision—at least until something better or more certain comes along.

Ultimately, most humans are often not very good at any of those last few items—we evolved with an unbearably weighty set of hardwired cognitive biases as social hominids hunting large mammals on the African plains—and these are difficult thinking traps to escape. That’s why science invented double-blind protocols—to help save ourselves from our own lousy observational abilities and poor critical thinking tools.

So I’m good with saying, and thinking, something like: “Well, I’ve thought about it, and ultimately this is the choice I’ve made, but I acknowledge that I’m guessing. I don’t really know how a snake thinks or feels or experiences the world, but I’m trying to take my best guess based on what little we know, so I can do the best job of taking care of it while enjoying the privilege of its company. I am willing to err on the side of what is best for the animal.”

I’m good with that. I’m not good with someone who, while fundamentally no different from me—who is taking their best guess, no matter how well intended—and is so absolutely certain that they have a personal handle on the One True Way, that they are willing to declare me and anyone else wrong, evil, or worse, for having come to a different conclusion.

Of course, if you’ve visited a herptile forum once, you’ve already met that person. But in the words of John Michels: “I’m always willing to learn.” I hope you are too.

There’s nothing wrong with that, and indeed it is at times a necessity, but—and this is a very important “but”—we need to always be self-skeptical, and simultaneously open to considering new ideas, and willing to change our minds. To pretend that we know the single correct answer with absolute certainty leads us to drown out other voices, to chase away legitimately interested parties from what should be a “big tent” of hobbyists, and fuels a stubborn sense of certainty that is often unsupportable by logic or currently available facts. It’s one thing to make an informed, reasonable guess. It is quite another to fail to distinguish between a sound guess and testable facts.

Hence you are welcome to the information provided on this page and website, the results of my own long experience and research, along with the work and thinking of countless other individuals. You are welcome to put it to use—and I hope you do!—and you are welcome to disagree with it. But it is not presented as the One True Way, and while I will try to indicate where certain conclusions of Indigo care are generally agreed upon, I will also try to be fair and present at least some aspects of multiple points of view where they exist and where there are legitimate disagreements and controversies. And while I don’t wish to drown this page in scientific papers—you can find those kinds of more extensive references on the Resources page—I will try to provide select research data in support of the conclusions and opinions presented here on the Husbandry page.

Finally, I am a professional writer (the author of six books), not a YouTuber. I tire easily of the endless river of what passes as “content” in the form of video, finding much of it boring, uninformative, at times downright silly and often just plain wrong. I recognize that reptile YouTubers will continue to garner far more interest than this website. There’s nothing I can do about that, but I will be clear: the original content and other resources of this website are primarily written. I write what I would want to find and read in my own search for advice and expertise. These husbandry pages essentially amount to an online book: Impeccable Indigos: “The Care and Maintenance of Drymarchon Couperi in Captivity”, by Jamy Ian Swiss. Like any good book, you won’t read it all in one sitting. But I hope readers and researchers explore the material, read and consider it, and above all use it—but if you’re looking for videos of teenaged “experts” frantically avoiding getting bitten, or actually being bitten, or otherwise prattling on endlessly on camera because they can’t or won’t write a sentence and their fans can’t or won’t read one anyway—you’re on the wrong site. I sincerely hope you’ll stick around here for a while, thought, and try something different. Who knows—you might like it, and you might learn something. I hope you do, because above all, that’s why this site is here.

-

There is no other snake like the Eastern Indigo, long considered the most desirable of snake species kept as pets, despite some of the challenges of maintaining them. When I was in the reptile and aquarium pet trade in the 1970s, despite handling hundreds of species of snakes, thousands of specimens, and keeping dozens of animals at home as well as breeding multiple species, I fell in love with Eastern Indigos and they became, and have always remained, my personal favorite. When I returned to the hobby after many decades’ absence, I no longer had any desire or intention to collect multiple species or large quantities. I simply want to raise Eastern Indigo Snakes. And among a select coterie of like-minded individuals, we will all quickly tell you of our shared obsession and love affair with this singularly extraordinary species.

The Eastern Indigo Snake (Drymarchon couperi) is North America’s largest native snake*, with the record being held by a specimen that was reputedly recorded as more than nine feet in length. Far more commonly, males typically reach to between seven and eight feet, and females (unlike many other snake species) typically end up about a foot shorter on average.

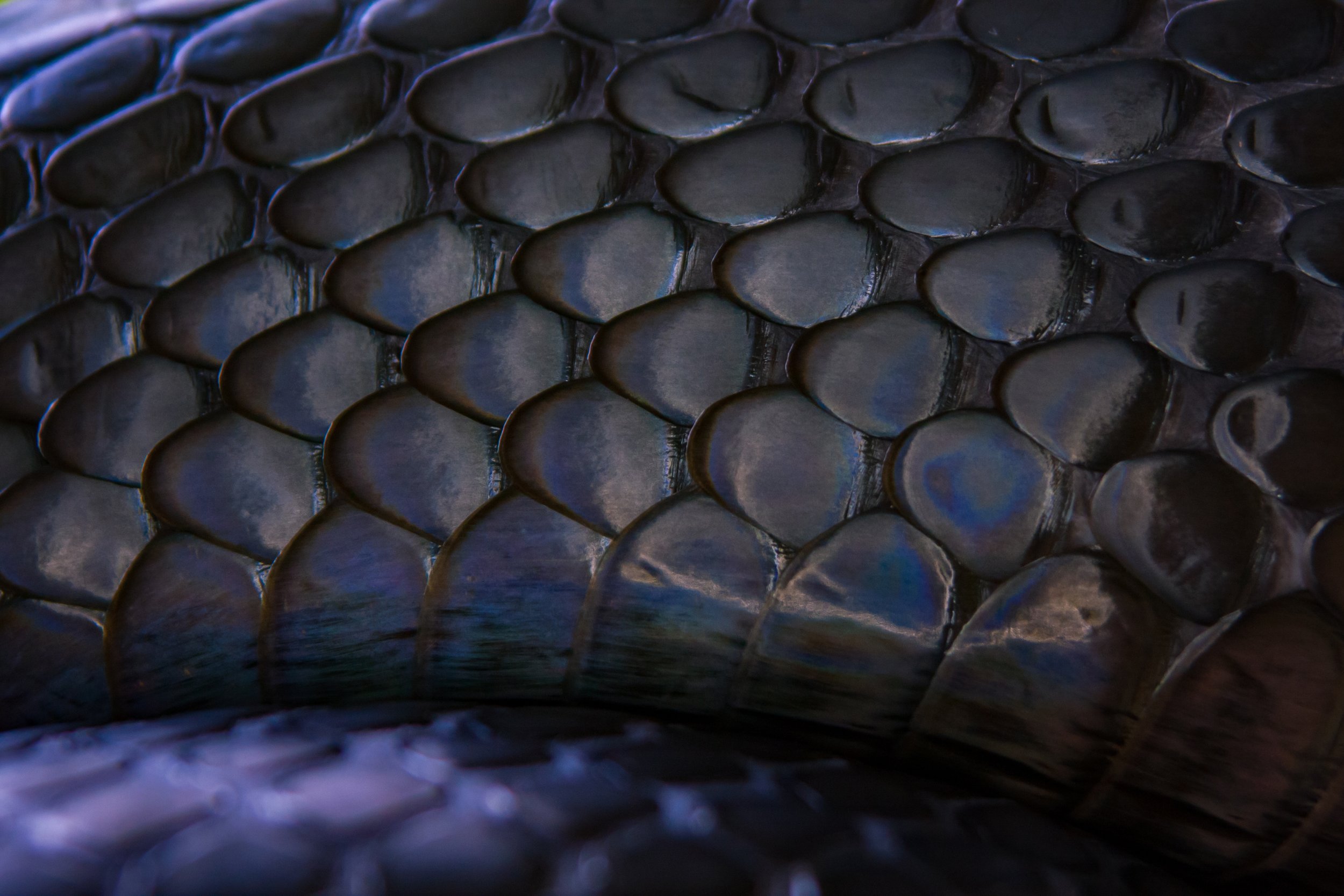

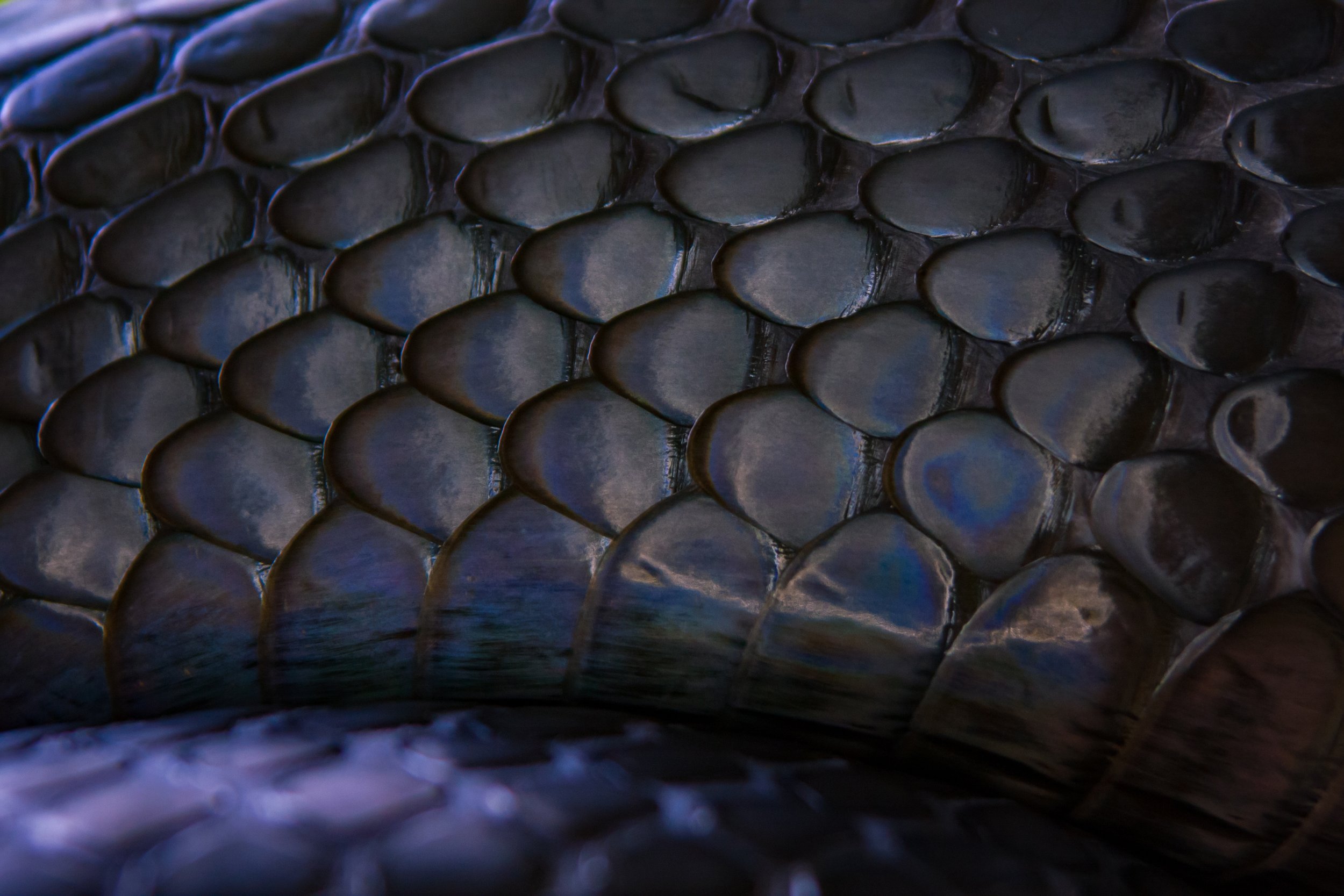

Indigo Snakes are essentially black in color, with variable red-to-rust or brown coloration on the lower side of the head and forward-most body. The black upper body, notably when illuminated in natural sunlight, shines with a scintillating blue-black iridescence that is the source of their common name, “Indigo.” Eastern Indigos also routinely appear in a second color phase, which while considered “black,” typically leaves some off-white coloration beneath the chin, however there is no red present. This is not a separate species or subspecies, it is merely a genetic variation, and any combination of parents that are red-to-red, black-to-black, or red-to-black, will frequently produce a mix of each variant among the young.

Indigo Snakes have scales that are smooth and large, notably on the head (not unlike King Cobras, with which Indigos share many traits, but Indigos are not venomous), and the Eastern Indigo is widely considered to be among the most uniquely beautiful snake species in North America, and indeed the world.

While their original range spread through northern and southern Florida into the Florida panhandle including Georgia and Alabama, their native range has been drastically curtailed over the past half century, due to over-collection for the pet industry (at one time) and primarily continual reduction of their natural habitat due to commercial development. In 1978, Eastern Indigos were placed on the Federal Endangered Species List and classified as a “Threatened” species, a status that they continue to maintain today. (On the Resources page you will find interesting information about efforts to restore the species to portions of its original range by introducing captive bred Indigo Snakes to the wild.)

Indigos are members of the Drymarchon genus, which are in turn part of the family of Colubrids, which are generally speaking relatively later evolved group of snakes than boas and pythons, and are invariably more slender bodied. While many colubrids are constrictors, and some are venomous, Drymarchon are distinctive in that they are neither. Rather, Drymarchon kill and consume their prey purely by overpowering them. Drymarchon have notably stronger jaws than most other snake species, and they will seize live prey and subdue it by any means necessary, perhaps a combination of slamming it against nearby rocks or similar, crushing with their jaws, and generally bulldozing the prey with extremely powerful and aggressive striking behavior that tends to grab the prey animal and continue to barrel forward until the prey strikes an obstacle, or the prey is otherwise overpowered and rapidly swallowed, sometimes while still partially alive.

Indigos are active diurnal animals that can cover distances of as much as three miles when hunting food or looking for mates. While venomous snakes are often ambush hunters—using natural camouflage and waiting quietly and still for long periods until prey comes into reach—Indigo Snakes are active hungers with strong vision. While many other snake species are extremely specialized eaters, Drymarchon in general and Indigo Snakes in particular are relatively eclectic in their tastes, consuming everything from insects and invertebrates for neonates, to fish, amphibians, lizards, snakes, birds, and small mammals. In the wild, other snake species are a particularly common choice of prey, including large rattlesnakes, one of the many reasons Indigo Snakes are valued by farmers and others who live in native Indigo territory.

Unlike most other snakes that consume whole animal prey, Indigos do not have flexible jaws and so are unable to swallow the large meals often taken by boas, pythons, vipers and many other colubrid species. Hence it is thought that for Drymarchon species, preying on snakes is an advantage because a larger meal can be consumed—a long slender prey animal being ingested by a long slender predator. As part and parcel of these behaviors and characteristics, Indigos and Drymarchon in general tend to have high metabolisms, needing to frequently eat relatively small meals rather than the infrequent large meals of species that can go weeks if not months between feedings.

This content is not intended as a thorough primer, and more information can be found on the Resources page under “More About Indigos.” What is most important perhaps about Indigo Snakes as far as hobbyists reptile keepers are concerned is my claim on this site that the Indigo is North America’s most charismatic snake—and actually I would say that it is likely the most charismatic snake in the world (perhaps along with the King Cobra).

This is because Indigos are not only beautiful, muscular, and magnificently impressive when at adult size, but they are generally agreed to be among the most intelligent of all snakes quickly taking in new information about new experiences, learning to recognize their keepers, and being generally curious and investigative about their surroundings. (It’s fair to say that King Cobras are similarly intelligent, and possibly Reticulated Pythons as well. However, such beliefs about relative intelligence are essentially anecdotal, even when based on extensive firsthand experience by keepers; that said, keepers tend to be biased toward their own favorite species.) What’s more, Eastern Indigo temperaments are unmatched, invariably growing into confident, commanding animals that are uniformly disinclined to bite. While Indigos, and more so other Drymarchon species, can be a bit of a challenge to handle because of their energy, strength, and curiosity, biting is not what one risks with an Indigo, even when in the hands of an inexperienced handler. While it is difficult to explain with certainty this consistent nature of this fantastically docile, thinking wild animal, one suspects that because adult Indigos are apex predators at the peak of their local food chains—their Latin name translates roughly to “lord of the forest”—their innate confidence prevents them from become defensive, whereas animals with more natural enemies can behave defensively, prone to strike or bite. Interestingly, King Cobras share many of these characteristics of the Eastern Indigo, including their strong vision and visual connection with the world, their thinking abilities, the fact that they are apex predators, snake-eaters, and even their ability to recognize and peacefully interact with their keepers.

[*Non-native invasive species, notably the Burmese Python in Florida, can exceed this size.]

-

Let’s begin with a clear statement: Indigo Snakes in particular, and Drymarchon species in general, are not beginner snakes. If you are just starting out on your snake-keeping journey, you should choose an easier, less demanding species, with which you can learn all the complexities of enclosures, heating, lighting, feeding, cleaning, and handling. For me, my preference for first-time snake keepers are corn snakes, of which there are countless varieties, and entry level prices are quite accessible, as there is no need to start off with the rarest of morphs. Other good entry-level species include some species of king snakes (Florida Chain Kings, as one good example, or perhaps California Kings). Rosy Boas are also excellent beginner pets. All of these species are hardy, generally easy to feed, and can be started in 24” or 30” enclosures and eventually moved to 48” enclosures (or optionally larger) as forever homes.

Ball Pythons are often touted as beginner snakes but I consider them borderline at best for this category, as they are more demanding in their living conditions (particularly requiring humidity), eventually require larger enclosures of at least 60” in length, and tend to go off feeding intermittently and unpredictably.

All of these species are far easier to keep than Indigos and other Drymarchon, as maintenance, cleaning and feeding are all far less frequent for rat snakes, king snakes, pythons and boas. All these species are also now commonly bred in captivity, and there is plenty of selection and ready availability. (One important note: Ironically and unfortunately, wild caught specimens are typically less expensive than captive bred animals, but with few exceptions, it is generally unethical to be taking animals from the wild today, given the ready availability of captive bred animals that do not impact wild populations, and ethical wild collection is the exception rather than the rule. There is justification for professional breeders trying to diversity their genetic lines, and a handful of dealers who have their own overseas facilities and stand behind the ethical taking of wild specimens, such as DM Exotics.)

But let’s get back to beginning your snake-keeping journey. Find out where the best specialty reptile shops are in your area, and if necessary be willing to travel a few extra miles, rather than buying your snake and setup from a national chain store (often abbreviated in hobby circles as BBPS, for Big Box Pet Shops). Support the businesses that will support you and your pursuit of the hobby; the reptile shop will have better information and a better selection of the right enclosures and maintenance tools and accessories that your animal requires. Also, watch for annual reptile shows, like the Reptile Super Show, that might come your way, and where you will find plenty of breeders and suppliers to talk, while being presented with a wealth of possibilities. But please—do not make an impulse livestock purchase! Ask questions, collect information, take notes, then go home and think about it all before you make a reasoned, dispassionate decision that will be best for both you and for your animal. Burmese Pythons, for example, are beautiful and generally very tame, but few people are prepared to keep an animal that can easily reach ten to twelve feet in length or more and requires an enclosure of a similar length or larger. And note that any of the snakes recommended here can live twenty years in captivity, with Ball Pythons reaching thirty years. This is not a casual commitment!

Indigo Snakes and other Drymarchon species are better suited to keepers with at least intermediate experience, with at least one but preferably perhaps with several specimens and species over a period of time of at least one or two years, in my personal opinion. There are multiple reasons for this. Indigos eventually turn into big, strong snakes, with females reaching six feet or more and males readily growing to between seven and eight feet. While they are absolutely not prone to biting, nevertheless they are more challenging to handle than corn snakes and ball pythons that tend to be very calm and not very quick moving (baby colubrids excepted), because Indigos are very aware of their surroundings, endlessly curious and frequently on the move. (This is even more true with other Indigo and Cribo species!) It takes some experience to be able to get a big Indigo to settle into your hands or arms and be still, without trying to forcibly restrain the animal with your hands, which you should never do (and which, with some of the other Indigo and Cribo species, can possibly lead to a frustration bite).

The one way you are most likely to get bitten by an Indigo or Cribo, and badly at that, is because all Drymarchon tend to develop extremely strong feeding responses as they mature. This is a risk with almost any snake, and keepers must learn how to detect what reaction is being triggered, and how to best communicate with the snake what is happening in the moments when an enclosure is first opened. Indigo Snakes don’t bite with the intent of aggression, but you can suffer a significant bite if the animal’s food response is unintentionally triggered and the snake misjudges the situation.

Further, Indigos and other Drymarchon species have much higher metabolisms than other colubrids, boas and pythons, with very young snakes feeding on small meals as often as every other day, juveniles every three to four days, young adults every four to five days, and full adults perhaps weekly. All that food is expensive and the costs add up, particularly when providing a varied diet of pricier foods like quail and Reptilinks. And all those feedings, combined with high metabolisms, means that Indigos and Drymarchon defecate far more frequently than other snakes. What’s more, many experienced snake keepers feel that Drymarchon feces are nastier and smellier (and unarguably less solid) than that of other types of snakes, characteristics which increase with the size of the animal and its meals; moreover, some individuals are in the habit of smearing the results widely around the enclosure and its side walls and glass fronts (albeit this is far less common with adults).

Indigos definitely do not like spending extended time with feces smelling up the enclosure and so enclosures must be cleaned continuously. Indigos also require a constant source of clean water, which must be changed regularly, and certainly any time a snake defecates in it, which some individual specimens are prone to do. And Indigos have very specific heating requirements which are the opposite of most other commonly kept captives, in that they do poorly at temperatures significantly above 83 degrees, and extended exposure to temperatures greater than 85 degrees can potentially result in fatalities.

To be clear, Indigos certainly experience these and higher temperatures in the wild, however they have the opportunity to thermoregulate. In captivity, where many enclosures may not vary in temperature at all, temperatures in the high 80s are dangerous for D. couperi. On the other hand, provided that you have significant temperature gradients in your enclosures — even within my 48” PVC unit I have managed to successfully establish multiple temperature gradients that vary from four to seven degrees from one portion of the unit to another. In this case, I can safely provide a basking surface that hits 90s as a benefit rather than a hazard to my animals.

It is widely claimed that Indigos can rapidly dehydrate without readily available water, which can potentially cause irreversible kidney damage. While the truth is that Indigos will at times deliberately go days without drinking, especially when hiding out during ecdysis, nevertheless fresh water should always be available in order to avoid risk, because it is true that many Indigos will simply not drink once the water is soiled, and occasional specimens may even decline water that is stale, hence it’s wise to change water perhaps twice a week to be on the safe side, and always immediately if soiled. (Also if an enclosure overheats due to heating malfunctions, a large water dish has saved many a snake as emergency refuge.)

Large size and active metabolisms also means that Indigos are constantly growing, and will begin to require sizable enclosure by the time they reach five feet, and permanent enclosures for full adults should be in the range of six to eight feet in length. Variety of stimulation and enclosure contents is yet another factor that will make for healthier Indigos over time in captivity. We are learning more and more about the value of enrichment for all captive animals throughout the evolutionary tree, and enrichment is now a prescribed element in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums specifications for more and more species, specifically including Indigo Snakes.

Thus while I am not trying to discourage you from pursuing the dream of living with an Indigo Snake, it is imperative that you plan ahead and are prepared to fully meet its requirements, more details of which are provided in the sections that follow. But above all, it is highly recommended that you work out your beginning snake experiences on hardier, less demanding species. My first snake was a Florida Chain King, and my youngest son’s first snake is a beautiful Albino Corn Snake that the whole family enjoys watching, handling and caring for. (You can find photos of him elsewhere on the site.)

-

But okay – let’s say that you’ve got some successful snake keeping experience under your belt, and you’ve considered all the requirements and preparations necessary to bring an Indigo Snake into your home and successfully care for it. Now what?

Unlike the aforementioned corn snakes, ball pythons, kingsnakes and other abundant and widely available captive bred snake species, Drymarchon are far less commonplace, and hence, far more expensive than many or most other snakes, save particularly rare morph varieties that fall into the Latest Big Thing category. Drymarchon are scarcer because there are far fewer breeders, and there are far fewer breeders because entry costs are high, and breeding is far from surefire or automatic—Drymarchon can be difficult to successfully breed and incubate. What’s more, some percentage of hatchlings will invariably be difficult to feed, and require a great deal of care and attention before being stabilized on readily available feeders—typically pinky mice to start, but many hatchlings must first be fed with whatever their stubbornly innate first preference may be, be it chick parts, fish, amphibians or other possible options, and then, with scenting, gradually moved to rodents. Throughout this process the snakes must be attended to and maintained by breeders for several months at the very least. Add up all of these considerations and costs of time, effort, food and more, and Drymarchon species in general are amongst the most expensive of captive bred snake species, with Eastern Indigos being more or less at the top limit of the price range (although some Blacktail Cribos and Mexican Redtail Indigos can demand similar price tags).

Who should you buy your Indigo Snake from? Although the number of small independent home breeders is definitely on the rise, most such breeders are fairly new to the game, and are breeding one or two pairs, without much history behind them, knowledge of their snakes’ genetic origins, or experience getting neonates to feed. There are probably fewer than a dozen breeders who are consistently producing Eastern Indigos every year and have track records for having been doing so for some significant length of time, and even within this small group, best guess is that most are breeding just a few pairs annually, perhaps producing not more than three to five viable clutches a year. Only two known breeders consistently produce more than this; both have been doing so for in the vicinity of twenty years, give or take, and both are located in Southern California.

Which brings us to another key complication when it comes to obtaining an Eastern Indigo Snake. Because the Eastern Indigo is federally protected, it is not only illegal to take any specimens from the wild (it is in fact illegal to even handle a wild specimen), but while captive breeding is legally permitted, Eastern Indigo Snakes cannot be transported across state lines without possession of a Federal Interstate Commerce permit (3-200-60 Native Endangered and Threatened Species Interstate Commerce). The permit costs a $100 fee and takes several months to process, yet another barrier to obtaining or keeping Eastern Indigos. However, you can legally transfer an Eastern Indigo within a given state, so if your breeder or source resides in the same state as you, you can forego the permit process. Keep in mind that the other Indigo and Cribo species are not similarly protected by federal law (Texas Indigos are protected by state law however), and hence are much easier to obtain, so for many, you may be well advised to consider another Indigo or Cribo species rather than facing the challenges of legally obtaining an Eastern. All the Drymarchon species are beautiful, and Texas and Mexican Indigos can often be quite similar to Easterns in most characteristics.

Most responsible Indigo breeders are prepared to provide several services:

Maintain hatchlings until they are consistently feeding and accepting rodent food (i.e. pink or fuzzy mice, preferably frozen/thawed).

Identify the sex of the animal you are purchasing.

Advise and guide you through the process of obtaining the federal permit if it is an out-of-state sale, and help see you through the planning and completion.

Answer questions and provide substantial information and guidance in preparing for your snake and initial care and maintenance.

Guarantee a snake without apparent flaws, such as spinal kinks or split scales, unless such conditions have explicitly been made apparent to you. In many cases, such conditions are otherwise harmless and animals with these characteristics can not only make excellent pets, but also can be obtained for a more reasonable cost, with the expectation that they will not and should not be used as breeding stock. (And note that these flaws are not necessarily the result of inbreeding or other genetic error, but rather are often the result of variations or failures in incubation conditions, i.e. temperature, humidity, etc.)

These are the minimum expectations that a potential purchaser should expect from their source, and if there is resistance or neglect in any of these areas, you should walk away and look elsewhere.

If it has not already become implicitly clear, I will make it explicit and recommend that in general you should not buy an Indigo from a retail reseller, i.e., a pet shop. You are likely to end up knowing nothing about the animal’s lineage or origins, and this is useful information to have (and indeed significant for the small percentage who are considering breeding in the future). Perhaps a retailer or reseller has a good relationship with a quality producer, but you will have to judge if you are getting sufficient and reliable information through that chain of communication; at best this might occur with a true reptile specialty shop, but while you are unlikely to ever find any Drymarchon in a major chain store or large general pet shop, if by some strange case you were to come across such an instance, I would leave that animal right there. You want to buy Drymarchon from breeders, not pet shops, just as you would or should buy a pedigree puppy from a reputable breeder, not a retail pet shop. Beware, especially online, of sellers who are not breeders but are merely “flipping snakes” for a quick profit, and are quick to overcharge while being short on knowledge or responsibility.

It is certainly possible that you might encounter a private individual who is selling an Indigo Snake, perhaps because they are moving on from their time and attempts with the species, for example. In such cases, if you are buying firsthand directly, you stand to be able to make a reasonably informed judgment.

But in the best of all worlds, you are better off seeking out experienced breeders who have a track record with Eastern Indigos, and are selling an animal to you that they produced themselves, perhaps from parents whom they have been breeding for years, or even since a previous generation.

How do you find those breeders? It will take a bit of effort. Your best bet is to join the Facebook communities that specialize in Indigos and Drymarchon, search through the history, note the names that repeatedly come up as known breeders, and then contact those people directly. Be willing to ask a lot of questions, and also to ask for referrals. Make sure you’re dealing with someone who is serious and reliable, who has a track record in the small community of Indigo and Drymarchon fanciers, and who will stand behind their animals.

All this will not happen in a day, and serves as yet another reason Indigos are not for beginners. You need to be willing to make a commitment—indeed, many commitments. But sincere efforts will eventually be rewarded, and the reward of being able to bring an Eastern Indigo Snake into your home is a reward worth waiting for.

-

I began above by saying I don’t much like care sheets. The problem is that many people think a care sheet is the last word on how to care for your snake, when it fact, a care sheet should only serve, at best, as an introduction.

That said, I have gathered some of the better care sheets available into this one convenient resource. I don’t think there’s a single entry that follows here that I completely agree with. (As just one example, there is much I like about the Everything Reptiles Care Sheet, but the instruction to feed Indigo Snakes every 7 to 10 days is wrong in my opinion. Indigos can go that long between feedings, but that should be an occasional event at most.) But is useful to study such resources and compare the details. If most agree on a particular point, there’s a good chance the recommendation is correct. If several disagree, that’s an item for you to flag and investigate further (and in such cases I have provided my own recommendations elsewhere within this husbandry page).

Some of these sheet also include additional information about biology and natural history. And I should state clearly here, for lack of a better place, that most if not all of these care guidelines apply equally to all Drymarchon species of Indigos and Cribos, and that while this site explicitly celebrates Eastern Indigos, in fact the entirety of the Drymarchon genus consists of wonderful species that are all very similar in most characteristics—and they are all beautiful and wondrous animals to keep and care for.

The final two items come from the two largest and longest-standing commercial Indigo Snake breeders in the U.S., both based in Southern California.

Eastern Indigo Snake Care Manual (AZA)

Eastern Indigo Snake Care Guide

Eastern Indigo Snake Care Sheet

Drymarchon Care Sheet (IndigoBlack) [I like this sheet and site]

Drymarchon Care Sheet (Black Pearl)

Breeding the Eastern Indigo Snake (Robert Bruce, 2015)

-

“Our study indicates that D. couperi is a predator of a wide diversity of animals, including invertebrates, fish, anurans, salamanders, small crocodilians, turtles, lizards, snakes—including venomous species—birds, mammals, and the eggs of vertebrates. Although certainly not dietary specialists per se, small turtles (including young Gopher Tortoises), anurans, rodents, and snakes figure prominently in the diet of wild D. couperi.”

— Prey Records for the Eastern Indigo Snake (2010 D.J. Stevenson et al.)

***

What to Feed

In the opening section of this page (“This is Not a Care Sheet) I stated that: “I will try to indicate where certain conclusions of Indigo care are generally agreed upon, but I will also try to be fair and present at least some aspects of multiple points of view where they exist and where there are controversies.” As we get further into husbandry issues, this proviso becomes increasingly relevant, and so it begins when it comes to feeding recommendations, as we will see shortly.

The reasons to feed dead prey (either freshly killed or, more typically, frozen and thawed) as opposed to live prey have been explained at length throughout the literature of captive snake husbandry since the 1970s, and needn’t be repeated here in any depth, but I will provide a succinct summary. Suffice it to say: It is fundamentally irresponsible to feed live prey in captivity. In addition to being cruel to prey animals, it is potentially extremely dangerous to the snake, which cannot control the hunting and killing circumstances as it can in the wild because of the constrained allotted space, in which even a small mouse can inflict a serious wound, and depending on the size of the snake and the size of the prey, easily even a fatal wound, all before it’s too late for the “watchful” keeper to have the chance to intervene. If you think watching a snake kill live prey is your idea of entertainment, please (a) get off my website, and (b) get out of the reptile hobby altogether, and (c) work out your personal problems elsewhere and in healthier ways. Seek therapy.

Feeding frozen and thawed (“F/T”) prey has been the standard of snake husbandry since the 1970s, an approach that came to the wider attention of hobbyists thanks to the great American herpetologist, Carl Kauffeld [https://second.wiki/wiki/carl_f_kauffeld], Curator of Reptiles and Director of the famed Staten Island Zoo, and author of three popular books (and countless technical publications) about snakes and snake husbandry. When I discovered his Snakes: The Keeper and the Kept (1969), it changed my life and the lives of countless snake keepers in the next decade, providing standards of care which I not only adopted for my own animals but utilized as my guide in education my customers and readers over the many years I sold snakes out of a retail pet shop and wrote articles about reptile husbandry, both for industry journals and pet magazines for the public. Among Kauffeld’s many innovations are included the reliance on frozen and thawed prey; on low humidity as a default; simple but thorough maintenance; and often newspaper as a recommended substrate. While these approaches have since evolved far beyond those of Kauffeld’s era (particularly regarding humidity and also variations in more natural substrates), nevertheless at a time when enclosures were often kept overly damp and in unsanitary conditions with dirt or other random substrate materials, Kauffeld’s recommendations become the standard not only for hobbyists but also for zoos for many years.

Hence when I first kept and bred Indigo Snakes in the 1970s, I kept them on newspaper, in screen-covered aquarium tanks topped with incandescent light fixtures for heat, and fed them on a diet of mice and then, when adults, small rats, all frozen and thawed. This has been the staple captive diet of Indigos, throughout their lifetimes, along with countless other carnivorous snake species, for decades, with little if any variation.

More recently, at least for the past decade if not longer, many Indigo and Drymarchon keepers, breeders, and professional institutions have come to the conclusion that Indigos should be fed a diet of varied vertebrate prey, including birds and fish along with rodents. Specifically these food items are provided in the form of readily available feeder animals including hatchling quail and larger, chicks, and fish (typically frozen “silver sides” for smaller snakes), all of which can be purchased from commercial suppliers. In addition, the rare keeper who has access to safe-to-consume feeder snakes will also add such prey to the mix when available, since snakes appear to be the foremost prey item for Eastern Indigos in the wild.

Even more recently, Reptilinks [https://reptilinks.com/] have come on to the marketplace, providing commercially available “sausages” filled with processed whole prey animals including frog, iguana, quail, and more. Although some snakes may be resistant to accepting this unnatural food format, Drymarchon in general and Indigo Snakes in particular appear to readily accept them, perhaps with the addition of appropriate “scenting” with previously preferred prey items. (Reptilinks even sells liquid scenting for the purpose, although I have never found it necessary.)

Why the change in dietary approach? One reason is doubtless the more ready availability now, as contrasted with the past, of alternate items such as quail and chicks. But a more significant reason is increased information and awareness about what Indigos eat in the wild. Although multiple studies dating as far back as at least 1944 confirm the varied diet of D. couperi, a noteworthy 2010 study, “Prey Records for the Eastern Indigo Snake” by Stevenson et al set out “… to bring together all available information regarding the diet of D. couperi in an attempt to answer the following questions: What types of prey are preferred? During what seasons/months does D. couperi forage?”

The robust study drew upon data from multiple sources, and confirmed among other facts that “Clearly, D. couperi are strongly ophiophagous” [feed on snakes] and that the “study corroborates the findings of Landers and Speake (1980), who reported that D. couperi preys primarily on amphibians, small Gopher Tortoises, snakes, and small mammals.” The results of the study state: “We compiled 185 separate vertebrate prey records for D. couperi totaling 47 species: 1 fish, 1 salamander, 3 anuran, 1 crocodilian, 3 turtle, 1 lizard, 24 snake, 4 bird, and 9 mammal species … . Anurans [frogs], Gopher Tortoises, snakes, and rodents accounted for 158 (85.4 %) of these records, with snakes accounting for 91 (49.2 %) of the records.” Following these four major prey types, D. couperi diet was also shown to include, in descending percentages: birds, lizards, crocodilians, caudate [salamanders and newts], fish, and invertebrates (with some evidence, as yet not definitive, that neonates tend to consume a significant portion of invertebrates in their diet]. In their conclusions the authors state: “Our study indicates that D. couperi is a predator of a wide diversity of animals, including invertebrates, fish, anurans, salamanders, small crocodilians, turtles, lizards, snakes—including venomous species—birds, mammals, and the eggs of vertebrates.”

The study also makes clear that individual snakes consume multiple species, which D. couperi are capable of foraging for over significant ranges and throughout seasonal changes and varying habits. The evidence is not that individual snakes specialize in a limited set of prey species that varies from individual to individual, but rather that D. couperi in general consume a varied diet.

These and other confirming results begs the question, do captive Indigo Snakes require a varied diet in order to thrive? And here is where some debate continues within the keeper and breeder community. It is clear that Indigo Snakes do not require a varied diet in order to survive and breed, as this has been clearly demonstrated over perhaps half a century or more, and there are breeders and keepers today who continue to feed their Indigos entirely on rodents. The AZA care manual states that, “In zoos and aquariums, D. couperi are normally maintained on rodent prey items,” however the AZA also takes pains to point out that “The manual should be considered a work in progress,” and elsewhere that “…we do not publish “standard” diets. Instead, we provide resources [emphasis per original] to help nutritionists develop diets.” And the AZA Indigo Snake care manual begins its chapter on nutrition with this as part of its description: “Drymarchon couperi are indiscriminate carnivores known to feed on virtually any vertebrate they can overpower.” Clearly, of the wild diet, there is no dispute.

Having said all that, however, there is a difference between “survive” and “thrive,” and increasingly, herpetoculture is moving in the direction, driven by multiple forces and elements within the community, of pursuing and providing the highest possible standards of care for captive reptiles, including all aspects of enclosure size and design as well as husbandry and, of course, diet.

This is not simply a vague wave of the hand toward an ill-defined ideal. Within a remarkably short period of time, knowledge of better husbandry and the tools with which to provide it have undergone remarkable growth. The data from both hobbyists and more rigorous scientific sources continues to pour in concerning a wide variety of species, the true facts of their wild habitat and habits, and rigorous data regarding the results of expanded and improved captive care. Not to mention the ever-increasing emphasis on the value of “enrichment” to render the lives of captive reptiles more interesting and mentally stimulating, in which case a varied diet can also be considered another aspect of such enrichment.

So, while we as yet lack specific data on comparisons between animals raised on strict rodent diets versus those raised on varied diets, we do have, first and foremost, clear and specific data concerning the natural diet of D. couperi, and it would appear advisable—and certainly by no means harmful!—to attempt to duplicate that diet with likely behavioral and health benefits accruing as a result. Keeping in mind that so much of reptile husbandry is a matter of collecting the best available data and then making the best available guess—there can be no compelling argument made against attempting to duplicate wild diets, even if one was to insist that the effort is possibly superfluous—which ultimately seems unlikely.

Also, however, we have increasing observational and anecdotal evidence provided by experienced keepers and breeders that a varied diet produces animals that are more robust, energetic, and produce better breeding results. John Michels of Black Pearl Reptiles makes this explicit claim in their care sheets, to wit: “Although many keepers successfully keep their Drymarchon on a rodent-only diet, I am a firm believer that the snakes are happier and healthier with a varied diet.”

In conclusion, as stated above, I have addressed and included “multiple points of view” and potential controversies, and in that light, I cannot state categorically that you should not keep your Indigos on a diet entirely comprised of mice and rats. However, I do recommend, as others increasingly do, and for the multiple reasons stated—if for no other reason, the interest and variety of experience for the snake—providing a varied diet. I feed my Indigos a regular diet mix of rodents and quail, of appropriate size, as well as chicks for adult animals that can take them, along with supplemental feedings of silver sides or other small whole fish, frog legs, and a variety of Reptilinks, primarily frog and iguana. (On the subject of fish, do not use “feeder goldfish” from the aquarium stores as they are invariably poorly kept and may carry parasites or other conditions.)

Also on the subject of feeding fish: I increasingly see some keepers feed chunks of fresh fish filet, such as salmon or other fish sold for human consumption. I do not at all see the point of this, and I prefer to feed whole animals for more complete nutrition, as would be consumed in the wild. Just because they will take filet doesn’t mean they should. As predators, snakes eat whole prey in the wild, gaining valuable and necessary nutrition not simply from the protein-rich flesh of prey animals, but including calcium from bone structures, and other nutritional elements included with internal organs. By feeding fish filet you are filling your animals with protein at the expense of these other ingredients — especially critically important bone and hence calcium — and with animals that eat once or twice a week, the imbalance in even a single meal of pure flesh is significant. I personally feel that there is no reason at all to ever feed fish filet. All the prey I feed is whole animal, including Reptilinks, and the only exception is the occasional feeding of frog legs, which while not whole animal, contain significant bone.

We cannot leave the subject of feeding without acknowledging that hatchling Indigos can be extremely unpredictable and inconsistent in their initial dietary wants and inclinations. While some neonates will immediately take live pinky mice, or live pinky mice scented with fish, many animals will refuse rodents at first and hold out for fish or even, in some cases, snakes, which appear to be the most natural primary diet for wild Indigos. Scenting with shed snake skins, fish, or frog will often get neonates to start taking rodents, and eventually they can work up to a consistent ease of acceptance without the scenting. Quail are often a favorite food, and neonates can be offered small quail parts at first. One must experiment until the animal eats, and then provide whatever is necessary in order to keep them at healthy weight, while then attempting to transition to more readily available items. All of this takes time and effort and your breeder is the first line of care when it comes to this process. Responsible breeders will generally not ship neonates until they have had at least three rodent meals, and this may take some time to accomplish.

HOW MUCH IS A MEAL?

Most experts are loathe to give precise recommendations for meal sizes, likely because opinions differ, and also, experience matters. Experience makes a difference because veteran snake keepers can judge a snake’s metabolism, behavior, weight, and growth rate, in order to judge feeding size and make adjustments in response to the particular animal.

That said, I will go so far as to offer some general guidelines, but pay attention to your breeder’s advice and don’t be shy about asking questions. That said, here is my simple, minimalist guide:SCHEDULE

— Feed juveniles every 3 to 4 days— Feed yearlings every 4 to 5 days until they reach about 3 to 4 feet in length

— At about 4 feet, feed every 5 to 6 days. Watch your animal’s weight, and if they appear to be getting “chunky” at any point, slow down the size and pace of feeding a bit.

— At between 4 to 5 feet, feed every 7 days. This is a good schedule as the animal continues to grow to maximum size.

— At full size, feed every 7 to 10 days. Indigos can go longer, but more frequent small meals are better than infrequent large meals. Indigos are NOT like constrictors!

MEAL SIZE

I feed growing snakes, from juveniles up to six feet, meals based on body weight. I feed a minimum of 10% of the animal’s body weight, and the younger and more growth producing the animal is, I will mostly stay within 15% to 20% of the animal’s body weight. These amounts, and the schedule pace described above, will provide steady and significant growth, without producing obese animals.

The animal’s body shape should not be bulging (except right after a meal) and there should not be much stretched skin showing between scales. In other words, scales should be close together; stretching indicates an animal is overweight. If the body shape seems triangular with a significant angled top edge along the spine, this indicates an animal is underweight. Snakes should be relatively lean but smoothly full bodied. Results will vary with individual specimens, with sex (males get bigger and grow more rapidly), and how much activity and exercise your animals get (I handle my animals very frequently and once they reach sufficient size and relaxed confidence — typically at about a year to a year-and-a-half — I take them outside regularly for exercise on the lawn). Because circumstances vary, if you think your animal is getting heavy, cut down the size of its meals.

Large meals are not good for Indigos as they cannot split their jaws the way most constrictor and venomous species can. Hence prey should not be much larger than the snake’s head, and should be about the same diameter as the snakes body (or smaller). A few smaller prey items makes for a far better Indigo meal than one large item. If your Indigo is taking more than three minutes to ingest its prey item, the prey is too large! Most of the individual items I feed are completely ingested within about one minute and often more quickly than that.

So in general I feed my animals 15% to 20% of their body weight until they reach six feet, and a minimum of 10%. I consider 10% to 15%, on the schedules provided above, to be a safe and healthy diet. That extra 5% produces consistent growth generally without tipping the animal to being overweight, but I will now and then vary the size and time between meals in order to maintain a proper weight range. Although many animals will take food when blue (preparing for shed), and many keepers will keep to regular schedules during this period, I typically stop feeding during the blue phase, to provide a bit of deliberate irregularity and a bit less intake from time to time. In other words, I use the animal’s shedding schedule as a way of consistently varying food consumption.

I also weigh my animals at every shed and in this way can plot weight growth as well as shedding and feeding schedules.

A FEW FEEDING DETAILS

DEFROSTING: Frozen food items can be defrosted in hot water — I typically microwave a jar of water for one minute, achieving a temperature of about 140 degrees. (You don’t want water much hotter than this, as you are using it for rapid defrosting, but you don’t want the heat to cook the prey animal.) I then submerge frozen prey in the water, about 10 or 12 minutes for large mice, rat pups, or weaned rats; button quail defrost a bit more quickly, and larger animals will require more time accordingly. You want to make certain that the internal organs of the animal are completely warmed and that you feel nothing sold or cold in the center of the body.

Defrosting in this fashion adds another level of safety with rodents in that the water serves to soften the otherwise hard and sharp claws of rodents.

RODENTS: In addition, I recommend crushing the skulls of rodents prior to feeding, in order to render them easier to digest, and lower the chance of intestinal blockages.

QAIL & CHICKS: Similarly, I crush the skulls of any bird prey. I also keep small scissors handy to clip the beaks and cut off the claws, again to render them safer to consume and digest.

SILVERSIDES: When tong feeding, try to maneuver things such that the snake will grab the fish by the head, as they go down much more safely, without risk of catching fins and spines internally if the fish is taken backwards. In my experience, if you are feeding from a dish, most Indigos will instinctively seek out the head.

FROG LEGS: Frozen frog legs are readily available in Asian markets. They need to be defrosted and, since they are quite large, I generally split them in half down the center with kitchen scissors, reducing their diameter for ease of ingestion. The cut hip bones at the top of leg are often quite large and sometimes possess sharp edges, and I will often trim this thickness down a bit before feeding.

REPTiLINKS: All of my Indigos, once they are steadily feeding, have readily accepted Reptilinks without the need for additional scenting. Initially I feed them off tongs to assure the snake seizing the link by the end for ease of ingestion. However with minimal experience, Indigos will typically readily take links from a dish.

TONG FEEDING VS. PASSIVE FEEDING: Elsewhere I have discussed the value of tong feedings, which helps to encourage a snake’s predatory behavior and keep their feeding response strong. Also, unlike constrictors which sense the warm body temperature of prey animals, Indigos hunt by scent but also like most snakes are particularly attracted to movement as a predation trigger, so tong feeding will quickly tempt a snake that may exhibit some disinterest in still food. Individuals vary in these behaviors. However, I also like to plant food around the enclosure, up in branches and within cork or cactus tubes, in order to compel snakes to hunt, a form of enrichment that stimulates the snake mentally. Many snakes will be more readily triggered if you feed the first prey item off tongs and then place additional items around the enclosure to be hunted down and consumed.

I will reiterate that prey items should not significantly exceed the diameter of the snake’s body. If it takes more than two or certainly three minutes to completely consume a particular prey item, you should reduce the size. Drymarchon are not like boas, pythons, and other constrictors such as rat snakes and king snakes, that can readily and safely consume prey significantly larger than their own heads. Don’t push big prey items on your snakes, even if they make the attempt or manage to consume such items given sufficient time. Make it easy on them with multiple, smaller items.

-

How to Feed

Do not feed your Indigo Snakes by hand. You are likely to get bitten, sooner or later, and you do not want to condition your snakes to associate your hand with food. Therefore, use large tweezers for very young snakes, and then once you’re feeding small to medium adult mice, switch to tongs.

It’s advisable to look for large feeding tweezers that have rubber-covered tips, so that a young snake does not injure its mouth or teeth. [See section 16, SOURCES, for these and other recommended items.] Larger snakes taking larger prey are more likely to strike the food more precisely and avoid the tips of the tongs if your placement is correct. An important detail regarding tongs is to obtain non-locking tongs, available from professional reptile suppliers; if you purchase from Amazon or similar general source, you will generally end up buying medical hemostats that latch or lock.

These should be avoided because they are difficult to keep from latching unintentionally, and if this occurs at the moment the snake strikes the prey, you will end up in a tug-of-war, or the snake may simply release the food and may then refuse it following this discomfort. Invest in quality snake feeding tongs; 12” in length will easily serve your purposes until snakes reach about five feet in length.

I am a big believer in “tong feeding,” among other reasons because it helps to establish a clear differentiation between feeding and other interactions. The tongs should only be present for feeding purposes and not at any other time, to help to condition your snake to associate food with tongs, as opposed to hands, and to be able to differentiate, the quicker and easier the better, between feeding as opposed to all other types of interactions.

Indigos are thinking animals that learn such associations quickly. My own rule is to present my snakes with two distinctly different kinds of interactions. Thus I engage in feeding this one way and one way only, every time: I take hold of the first prey item in the tongs in readiness; I then open the enclosure and instantly present the food for the taking. This is always my first step in feeding.

When there are additional food items, depending on the snake I will generally quickly place other food items around the enclosure, in branches or on rocks, so that the animal can gain a bit of enrichment by hunting and finding these items on their own. Or, with wet food like silver sides or Reptilinks, I may simply set the rest of the food into the enclosure on a small feeding dish, and the snake will proceed to find and readily consume these items (believe it or not!).

Some keepers feed their snakes in a separate feeding location or container, thus keeping feeding behavior entirely separate and away from the main enclosure. While I am not persuaded that this makes any difference in preventing potential bites from triggering feeding responses within the enclosure, one possibly valid reason to use this approach is that it prevents the accidental ingestion of loose substrate; that said, I have rarely experienced Indigos accidentally ingesting substrate, as the structure and shape of their mouths is such that it is naturally shorn away as the prey is consumed; what’s more, it seems unlikely that occasional bits will cause any harm as certainly animals consume their share of dirt and debris in the wild.

I do know some veteran breeders and Indigo keepers who adhere to the separate location feeding method, and so I am reminded of John Michels’ words: “If something different works for you, that’s great.” However, I have never used this approach, and while I think it’s a perfectly fine thing for keeping feeding away from the main enclosure, I will address several other related concerns and objections.

One potential concern is that in the case of snakes that are picky or inconsistent feeders, or young snakes that are not yet settled into eating readily and consistently, for my money the last thing I ever want to do is add another variable or potential stressor to the feeding process. Granted, once Indigos are genuinely steadily feeding—not just having taken multiple meals but that have reached the point where their feeding behavior is consistent, predictable, and once triggered, is immediately aggressive without any uncertainty—they are generally not a species that is going to go off food unless there is a medical issue or the behavior is breeding related (i.e. gravid females). But very young Indigos can take awhile before they reach this stage of becoming solid and consistent feeders, and until such time, I am not under any circumstance going to move them from their comfortable resident enclosure or inflict any change connected with feeding.

I believe most Indigo keepers, even those who do utilize separate feeding containers, would likely agree with the above, and probably do not move their young snakes until they are feeding steadily. (If I am mistaken about this assumption, I would be interested in knowing otherwise.)

However, there is another belief I have often heard promoted among keepers of Indigos or other species who claim that tong feeding—which includes encouraging a snake to strike its prey, rather than passively take food from the cage bottom or a dish, or a separate feeding location or container—somehow encourages aggression in the animal’s nature and personality.

This is, in my estimation, fundamentally nonsense, and what’s more, it strikes me as misguided. Your snake is a predator; why on earth would you want to try to pretend it’s a bunny rabbit? The fact is that I want to maintain that natural feeding aggression—emphasis on both words here, feeding aggression—so that the animal doesn’t suddenly stop eating because of the smallest change or disturbance in its conditions or feeding pattern. I want my snakes to be aggressive feeders—which, especially with animals as intelligent and quick to learn as Indigos Snakes, has absolutely nothing to do with the animals being aggressive in any other context. In short: They quickly learn the difference, if you make it clear to them. If you don’t want a predator to act like a predator, don’t own a predator. Get something predators eat—a gerbil, hamster or a rat—and keep that as a pet instead. Do not inflict your own fears and biases on your innocent captives.

Tap Training

Most experienced snake keepers (and this applies to many species) can be readily “tap trained,” meaning that when you are about to engage in any non-feeding interaction, and you wish to quickly disarm the snake’s feeding behavior, you gently—very, very gently and briefly—touch (it’s really a “touch” rather than a “tap”!) the snake on the nose with a snake hook (and don’t use a hook any heavier than is necessary for the size of your snake; light compound hooks are preferable to weighty metal hooks). Snakes in general and Indigos in particular will quickly learn that this touch of a hook means there is no food, and thus their feeding trigger is instantly negated.

This is a fascinating phenomenon to see with Indigo Snakes, and it doesn’t take them very long to figure it out. If my Indigos are hungry, they are generally out front looking to be fed, and when the enclosure is opened you can clearly see (once you know how to recognize it) that they are alert, energized, and poised for the kill, as it were. (If you’re not careful, some may even come rocketing out of the enclosure as if launched!) And, if you are not very careful in this instant, you will get bitten—but it is important to understand that this is not an act of aggression, or fear, it is a feeding response. However, in this instant, if you touch the snake with the hook, you can see them stand down. They instantly calm down, and their entire body posture alters. In essence, they relax.

Because of the potential for a swift feeding reaction, it is wise with Drymarchon to use a hook as first contact, not only to “tap” but also to pull the snake from its location, and partly out of the enclosure. The combination of the tap and the hook means that in the seconds between the initial contact and getting the animal in your hands, it knows already that feeding is off the table, and it will remain calm and prepared to be handled. It is wise to make this a firm habit with Drymarchon, because a bite, no matter the cause, can be a painful and messy thing, thanks to sharp teeth and the unusually strong jaws of these particular species. Better safe than sorry. Make the hook a safety habit.

To make my approach completely clear, if I am feeding, I make sure to be able to instantly present food, on tongs, the moment the enclosure is opened. The animal’s feeding response is properly triggered, and the meal ensues.

However, if I am not feeding, I make sure to keep tongs entirely out of view, and if my intention is to handle the animal, I will typically promptly introduce the hook for a tap or a body touch or both, and then put it aside. However, oftentimes if my intention is to do spot cleaning, water replacement, substrate maintenance or any such task other than handling, then I use my judgment as to whether or not to tap or touch before proceeding. If the animal is up and active and seems prone to a feeding response, I will tap or touch in order to disarm that. However, because my animals are accustomed to food only being an instant presentation upon opening the enclosure, most of the time my snakes relax the moment I start doing anything in the enclosure that is not feeding or handling. In other words, the simple fact of delaying—the lack of tongs and food being presented at all—more often than not will cause the animal to recognize within a few moments that this is not a feeding interaction, and so even without tapping or touching or moving them, they will visibly relax and ignore me, or watch what I am doing with some curiosity, but without any feeding response being triggered. While it is true I am taking a small chance in these situations, the delay is typically enough for the snake to recognize that this is not a feeding. But under the heading of better safe than sorry, depending on the size of the enclosure, tap or touch is always the safer way to make sure you have given the animal a clear message, and that it has not missed the intended message.

So, my experience (and the experience of many others) clearly demonstrates that if you distinctly separate feeding from other interactions, and also “tap train” your Indigo Snake, there is neither need nor provable value in moving a snake to an alternate feeding location. That choice is yours, but my choice is to avoid this procedure entirely.

Target Training

Finally, while the kind of training I have described is minimal and straightforward – and quicker and easier for Indigos to apprehend than for many other species, although most will eventually, with consistency, get the idea—there are more detailed, nuanced, and varied forms of training snakes available to you, and thanks to their ready intelligence and visual acuity and attentiveness, Drymarchon should likely respond to these methods well. Operant conditioning, commonly known as “target training,” has long been used with wild animals in professional zoos and aquaria, in order to train animals not merely to do performance behaviors, but to create and command behaviors that are useful for facilitating care procedures and reducing stress in necessary captive maintenance procedures. Thus, for example, many animals are trained to move or “shift” between enclosures as needed, to submit to certain kinds of handling for medical care, or to enter into specialized containment for veterinary procedures, medications, examinations and the like. The term “target” refers to the fundamental tool of training, which is generally some form of a colored ball or similar, too-large-to-swallow object on the end of a stick, which the animal is trained to follow or touch with its nose or some other body part when presented, in return for which the animal receives a food reward. Once the target training is achieved, the target is then used to build beyond the basic contact into more elaborate, multi-step behaviors.

While these techniques have been used for decades with mammals and birds, increasingly we are finding that such techniques can be used for an extraordinary array of animals, as we move down the evolutionary ladder to species traditionally regarded as less complex or intelligent. And currently there is increased awareness and interest in using these techniques with many reptile species. For further information about target training snakes and other reptiles, I refer you to the work of Lori Torrini, and her YouTube channel [https://www.youtube.com/c/LoriTorriniAnimalBehavior] and also Reptelligence.com and their associated YouTube videos. The value of target training snakes is multi-faceted; with giant snakes and venomous species, it makes sense to train an animal to move from one enclosure to another space or container with a minimum of direct handling, or no direct handling at all. The usefulness in these instances is unarguable. But there is something to be said for the notion that training any snake can be fun and interesting for the keeper, and enriching and mentally stimulating for the snake. I therefore encourage your further exploration of target training and its techniques, the details of which are beyond the scope of this site’s focus.

-

Permanent Home Enclosures for Adult Indigo Snakes

As with every aspect of reptile husbandry in recent years, ideas about enclosures, and available options, have significantly evolved. The first question when it comes to large snakes like Drymarchon, as well as larger boas and pythons, is “How large an enclosure is needed?” And the answer has definitely changed in recent years.

Along with the increasingly operative assumption that reptile keepers should strive to approximate a naturalistic living conditions as possible, while acknowledging that the actual space limitations of captivity are by definition extremely constraining, increasingly there is a trend toward enclosure sizes that allow a snake to stretch out for its entire length. While there is debate about how routinely snakes do this in the wild, there is increasing evidence that given the opportunity, they will extend their entire length from time to time.

Two leading contemporary rule-of-thumb recommendations concerning enclosure size for adult snakes are:

1) The length of the animal should be equal to the length plus width of the enclosure. So an enclosure that is six feet by two feet is appropriate for an eight-foot snake.

2) The length of the snake should be equal to the diagonal length of the enclosure. So an enclosure that is six feet by two feet is appropriate for a snake that is seven feet, four inches in length.

So you can see that while both of these formulae produce somewhat similar results, the diagonal guideline clearly requires a larger enclosure for the same size snake. By comparison, the diagonal of an enclosure that measures eight feet by two feet measures eight feet, four inches.

In November of 2021, the Federation of British Herpetologist (FBH) issued their 44-page Code of Practice for “Minimum Enclosure Sizes for Reptiles,” probably the most progressive and thorough such set of standards currently available (albeit which still has its vocal critics), from which I will quote at some length. In the document’s opening pages, under the heading “Rationale,” the document states: